Martin Moore

Every now and then, your research will turn up a source which so perfectly embodies your research interests that you can’t wait to share it with colleagues.

I had this experience recently when looking for material for my current work on the physiological balance strand of this project. Searching through the collections of the Wellcome Library, I came across this particularly fascinating video:

http://wellcomelibrary.org/player/b1665853x#?asi=0&ai=0

It was produced in 1959 in association with the Hammersmith and University College Hospitals of London, and aimed to walk a particularly thin and challenging clinical line: introducing newly diagnosed patients to the causes and dangers of diabetes, as well as covering its treatment and reassuring them of its manageability.

Of course, the video and its origins can be interpreted in any number of ways. Its hospital production could be seen as highlighting the prominent role of this institution in the care of patients. Its introduction of clinician and dietitian could be seen as evidence of expanding hospital care teams. Or its very existence could be read as testament to yet another way in which diabetes and its care has sat at the forefront of technological and clinical innovation in British medicine.[1]

Diabetes and the Culture of Capitalism

For me, however, it seemed to lay out perfectly how social and political norms have historically been embedded – or in the terms of theorists like Stuart Hall, been encoded – within instructions for ensuring physiological balance, as well as indicating how normality has provided a mechanism for encouraging patients to follow medical advice.[2] Examples can be found even within its first minute.

The video opens, for example, with images of passengers alighting a train, and pedestrians and shoppers passing down a high street. Over the top of these images we hear an RP-accented narrator inform viewers that diabetes is a condition that affects approximately 3 out of every 200 people in Britain, or 6 in every crowded train or street. However, the successfully “balanced diabetics”, we are informed, “go unnoticed in the crowd. They no longer suffer from diabetes, they have learned to manage the condition and they live usefully and normally with other people”. (00.00.43 – 00.01.09)

Ostensibly, the images of passengers, pedestrians and shoppers are included to ground potentially abstract figures of prevalence into familiar and concrete situations. A potentially “silent” disease with a prevalence rate of 1.5 per cent is thereby transformed into a condition that affects on average six people on a train – perhaps people viewers may know and with whom they regularly travel.

Along with the narration, though, these images also serve to represent and reinforce a particular view of normality. Pictures of well-heeled commuters, for instance, clearly link the notion of the “useful” individual to figures of the productive, though professional, worker, whilst footage of shoppers and high-street stores juxtaposes and implicitly connects normality to acts of consumption. The latter likely being a powerful image given post-war Britain’s recent boom in consumer goods, and recent relief of rationing.

Moving attention away from an undifferentiated, supposedly normal populous in this footage, and speaking to the newly diagnosed viewer, the video then promises that such lives and activities can (once again) be in reach of the diabetic if they are “well-balanced”, patently tying the importance of maintaining physiological balance with desired social normality. It is, moreover, a normality consistent with the values of professional work, consumption, and individual responsibility central to the political and economic logic of contemporary British capitalism, then characterised by a certain hybridity. That is, a liberalisation of production and consumption in some markets, but a cultural tendency towards professional economic management and planning more generally.[3] The culture of medicine, in other words, was clearly influenced by the political, social and economic context within which it took place, as well as to emergent themes of individualism in public health medicine more broadly.[4]

Normality, Balance and Patient Discipline

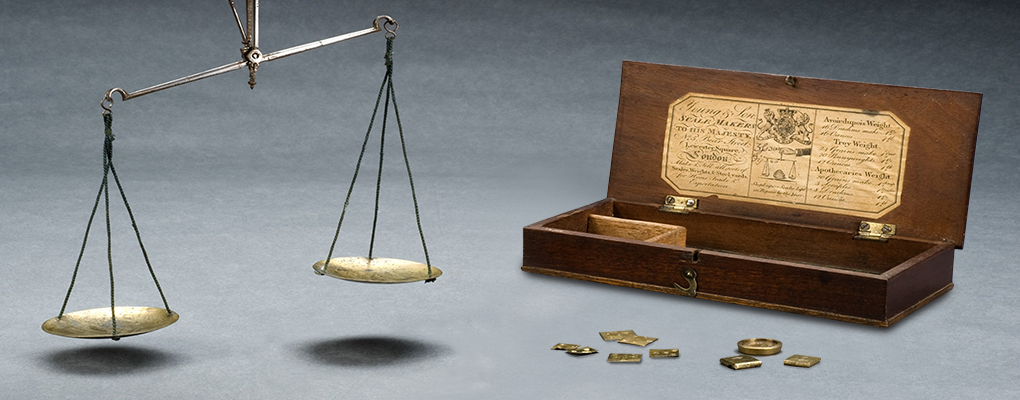

The link between physiological balance, normal social lives, and following medical advice is strengthened a few minutes later in the video, after the doctor has – with the help of some animated scales – described the cause of diabetes as resulting from an imbalance of insulin, dietary sugar and “our requirements”. (00.01.27-00.02.17).

In a subsequent exchange, a dietitian seeks to stress the importance of weight reduction to achieving balance in conversation with a stereotypical “fat” diabetic (to use the video’s terms. Interestingly, this type of patient is represented by a businessman from “the city”, Mr Anderson). Initially, upset by his new dietary prescription, our dietitian interrupts Mr Anderson’s efforts to relate his weight and diet to working conditions, and overcomes his resistance by suggesting that “this [diet] is going to alter your habits, but it won’t be the end of the world for you, and you must do it for your own sake”. (00.03.55-00.04.45). Initially, concerned by the extent to which his new diet might alter his activity at important business dinners, Mr Anderson is begrudgingly convinced by this argument and attention turns to “our thin friend”, Miss Smith (00.04.45-00.04.50). Accepting medical advice, therefore, Mr Anderson was now in a position to balance his physiology, and though this required some alteration to dietary practice, it would benefit himself and allow him to perform his broader role in society.

Future Research

In the future, I hope to be able to follow-up my interest in these representational devices with further research into their use and reception. Through oral history interviews with patients and practitioners, as well as other material, such as magazines and medical journals, I hope to trace how various actors decoded these messages.[5] To ask, in many respects, what the limits of medical intervention and regulation were.

I will also look to broaden thematically into questions of gender, class and ethnicity. This video, for instance, is very much focused on patients seen at the time to occupy the Registrar General’s classes I-III (then deemed the most liable to diabetes), and on white patients, despite the presence of black individuals in both British clinics and the video’s non-medical footage. I want to know when such material altered its boundaries in this respect, and to map this onto the changing demographics of treatment. Similarly, although it raises interesting questions about the power of gender ideals and assumptions in shaping practice, I hope to trace how such ideals affected patients, and how they changed over time.

[1] For a short and accessible overview: R.B. Tattersall, Diabetes: The Biography, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009). For a more in-depth, but very engaging view of this history in the US: Chris Feudtner Bittersweet: Diabetes, Insulin and the Transformation of Illness, (Chapel Hill: University of Carolina Press, 2003).

[2] For an introduction see: Stuart Hall, ‘Encoding/Decoding’, in Meenaskshi Gigi Durham and Douglas M. Kellner, Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks, 2nd Edition, (Oxford: Blackwell, 2006), 163-73.

[3] For an introduction to debates about post-war economic policy: Neil Rollings, ‘Poor Mr Butskell: A Short Life, Wrecked by Schizophrenia, Twentieth Century British History, Vol.5, (No.2, 1994), 183-205. And on planning and professionalism: Glen O’Hara, From Dreams to Disillusionment: Economic and Social Planning in 1960s, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007); Harold Perkin, The rise of professional society: England since 1880, (London: Routledge, 1989).

[4] On contemporary developments in public health, and regulated individualism: Virginia Berridge, ‘Medicine and the Public: The 1962 Report of the Royal College of Physicians and the New Public Health’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol.81, (No.1, 2007), 286-311; Dorothy Porter, Health Citizenship: Essays in Social Medicine and Biomedical Politics, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011, 154-181.