In this post, Nicos Kefalas (a PhD student with the Balance project) discusses his doctoral research into healthy eating and supplementation. Here he considers why self-help books about diet became so popular in the post-war period, and examines the ways in which this literature deployed linguistic devices to construct readers as “empowered” agents of healthy-lifestyles.

In recent years, it seems that not a day passes by without public debate about healthy eating and supplements. Thousands of magazines, newspapers, websites, YouTube videos and blogs are dedicated to issues revolving around food, diet, exercise, supplementation and health. Popular discussants of healthy diets even make use of data from randomized-control trials (RCTs) and population studies, metastudies and large trials, and translate such knowledge into easily digestible graphics on various foods and supplements to demonstrate whether or not they are truly good for overall good health. (Or to weed out products that could be considered as ‘snake oils’).[1]

My PhD examines the historical emergence and development of healthy eating, dietary advice and supplements to provide a better understanding of when, how, why and by whom ‘Healthmania’ was promoted. [2] ‘Healthmania’ is the fascination of various institutions of the West with healthy diets, foods and supplements, and the concomitant production of advice and products to help individuals attain better lifestyles, both independently and collectively. From the 1950s onwards, self-help literature, lifestyle magazines, newspapers, advertisers, science and the state accepted and promoted certain foods, diets and supplements for a number of reasons. Building upon a widespread valorisation of science on the one hand, and fascination of the media and public with slim bodies and healthy lifestyles on another, leading scientists, public figures and state bodies were all motivated by a mixture of personal ambition and broader political aims to promote healthy eating and supplementation.

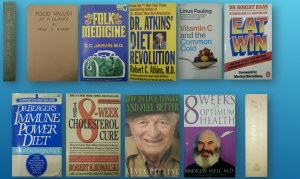

Following historical work on Galenic medicine, food and health that has centred on early-modern herbals, manuals and cookery books, I am currently examining English language self-help books published between 1950-2000 which concentrate on nutrition, diets, food and health.

‘HEALTHMANIA’ IN SELF-HELP BOOKS’

Self-help authors made individual agency central to their efforts to popularise ‘optimal’ and ‘ideal’ diets. It is clear that the language and advice in self-help books emphasize and promote the notion that readers have the power to manage their own health and a moral obligation to do so. The books heavily imply that the proactive, educated, well-read and well-informed individual can promote their own good health. The readers are initiated into a self-narrative in which they do not need or want the help of doctors and expensive or ineffective treatments. This newfound agency over their own health is reinforced by the growth of capitalism to provide the foods and supplements necessary to sustain a mentality of ‘buying a better body’. Indeed, not only does the self-help literature direct its readers to the nearest health food stores, pharmacies and juice bars, but it also urges readers to consume specific foods (often exotic fruit), drinks and supplements. Some authors of self-help guides even take a further step. For example, Dr Atkins urges his readers to monitor their progress using a home urine-chemistry kit, encouraging the purchase of sophisticated surveillance technology, alongside expensive dietary consumables and further literature.

One of the reasons behind the popularity of the self-help industry lies in the fact that it stood out from mainstream science and advice for better health, which often consisted of the mantra to ‘eat less, exercise more’. By contrast, whilst self-help books sought to empower readers to make positive changes in the present and future, self-help books nonetheless removed the blame for ill-health and obesity from their readers and instead attributed responsibility for past failures to the food industry, ‘modern foods’, fast foods, mainstream science, and modern lifestyles. Each reader is thus given the chance to feel like a revolutionary and an ‘enlightened’ consumer. This narrative was facilitated through the consistent use of motivational language, tone, expressions and symbolism. Taking Atkins’ book as an example once more, one can see how phraseology and capitalisation of sentences urged his readers to stop being bystanders to the damage done to their bodies by modern foods (namely carbohydrates in this case) and start defending their health. Such phrases were ‘A REVOLUTION IN OUR DIET THINKING IS LONG OVERDUE’ and ‘WE ARE THE VICTIMS OF CARBOHYDRATE POISONING’.[3]

People turned to self-help books because they addressed contemporary anxieties of the everyday individual. The fear of hunger, for instance, is explicitly addressed by the genre as a whole. These authors knew that people fear hunger, because when they are hungry they lose their control of their bodies, and compromise their diets with filling – though not necessarily healthy – foods. In the short-term, authors reassured readers, this was not necessarily an issue. As Robert Haas advised his readers: ‘There is no point in worrying about cheating occasionally’. He noted, however, that such infidelities to his rules were only acceptable if ‘you stick to the Peak Performance Programme in the long run’.[4]

Yet, alongside questions of deprivation, self-help authors had another, seemingly paradoxical, problem to think about, – luxury and efficiency. No one wants to start a boring diet that does not bring the desired results fast enough. Produced at a time when instant gratification of nearly all desires, cravings and wants can be quite simply achieved, self-help books had to portray eating healthily as an easy process coming from filling, varied, tasty and luxurious foods. For example, Atkins argued that people could lose weight on: ‘Bacon and eggs for breakfast, on heavy cream in their coffee, on mayonnaise on their salads, butter sauce on their lobster; on spareribs, roast duck, on pastrami; on my special cheesecake for dessert’.

These and many more themes in the self-help genre play a big part in the popularisation of science and the growth of ‘Healthmania’. The readers of these books are given the knowledge to become active agents of their own health. Change towards better health is elevated to an individualistic and stoic process by which the readers refused to be ill, overweight or obese. The process of becoming healthier offered by the self-help genre is easier with less hunger and more ‘exotic’ and luxurious foods than the average diet recommended by the state and doctors. The advice in these books offers readers a way to avoid the dreaded visits to doctors’ practices, and thus on the surface at least, serves in part to undermine the authority of orthodox medicine. However, even though these books seem to have been against modern scientific theories/practices, self-help authors were using contemporary scientific ideas. These authors offered a self-criticism of the various food and health-related professions they wrote from. They did so by using widely accepted scientific tools and perspectives to criticise orthodox medicine and dietetics from a marginal perspective. Indeed self-help books promoted their advice by using the same tools and analytics (macronutrients, micronutrients, calories, specific foods and supplements, the culture of quantification, and often their authors underwent the same training as their ‘mainstream’ counterparts). By following the advice offered by these books, the readers break out of the complacency to ill-health imposed on them by ‘modernity’ and became part of a reactionary kinship. In these works, health itself became a rational, measurable and quantifiable endeavour. More significantly, though, it became a commodity, leading to the explosion of the supplement industry and ‘Healthmania’ in general.

[1] For instance: http://www.informationisbeautiful.net/visualizations/snake-oil-supplements/

[2] This notion goes beyond the 1980s term coined by Robert Crawford, called healthism which is: ‘the preoccupation with personal health as a primary – often the primary – focus for the definition and achievement of well-being; a goal which is to be attained primarily through the modification of life styles’.

[3] R.C. Atkins, Dr Atkins’ Diet Revolution (New York, Bantam, 1972), pp. 3-5.

[4] R. Haas, (British adaptation by A. Cochrane), Eat To Win (Middlesex, Penguin, 1985), p. 157.